President's Message

We are very saddened by the death of The Reverend Dr. Robert (Bob) Bluford, Jr. on April 30, 2022.

The Henrico County Historical Society is honored to have an association with Dr. Bluford. He served as president from 1991-1993. The world has lost a great champion of historic preservation. He lived a remarkable life in his 103 years.

Dr. Bluford's education was interrupted by World War II. He served his country as a B-24 bomber pilot in Europe after which he returned home to Richmond to finish his education and later became a Presbyterian minister. He had a special interest in historic preservation and his accomplishments were many, likely too many to list in this space. He was responsible for having the Laurel Historic District of Henrico County listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was instrumental in the preservation of Richmond-area battlefields. He cofounded the Fan Free Clinic in Richmond in 1968 and led the movement to save the pre-Revolution site of Polegreen Church.

That project began when a highway marker caught his eye, while driving through Hanover County. He couldn't read it as he drove past, so he parked and walked back. The sign noted the site, which in the 1740s became a critical setting in the colonists' struggle for religious liberty. The Rev. Samuel Davies, Virginia's first licensed non-Anglican minister, preached at the church and was noted for "inspiring one of his young congregants, Patrick Henry."

An interview by Bill Lohmann in the Richmond Times-Dispatch quoted Dr. Bluford in reference to Polegreen Church: "I just kept thinking about it . . . It got on my agenda, and never got off."

Dr. Bluford was the recipient of the 2004 First Freedom Award bestowed by the Council for America's First Freedom for his work. Polegreen Church is now an important stop for visitors along the state-designated Road to Revolution Heritage Trail.

Bluford was also active with the United Indians of Virginia's effort to recover nearly 2,000 skeletal remains of their ancestors from the Smithsonian Institute.

He was elected to the United Indians' board of directors and is the only non-Indian to be recognized as a board member. He was honored by the Virginia General Assembly in 2004, and in 2008 received the Carrington Williams Battlefield Preservationist of the Year Award from the Civil War Preservation Trust. He received the Virginia Press Association's Virginian of the Year Award in 2011.

Bill Loehmann's interview also noted that "he said he's just as happy seeing the everyday impact of his work, such as when he was at historic Polegreen Church raking leaves on Sept. 11, 2002, one year after the terrorist attacks.

He looked up and noticed a woman sitting with her back to one of the steel beams of the church's framework.

"I could see her head was bent down like she was praying," Bluford recalled. "Later she was walking to her automobile, and she saw me and said, 'I hope it was all right of me to be here this morning, but on this anniversary, I felt like I just wanted to be in a place like this.'

"I thought, 'Man, this makes raking leaves worthwhile."

Polegreen Church (located at 6411 Heatherwood Drive, Mechanicsville, VA) is an open-air sculptured design. The original church was destroyed by fire during the Civil War.

"One thing for sure I can say about my life, ... I didn't suffer from boredom," Bluford said with a laugh. "Always something to do. Something worth doing."

At age 65, he ran his first of other marathons.

We honor those who are an inspiration to carry forth the legacy of "something worth doing." Who knows where that will lead …. just as Patrick Henry was inspired. Always much to do!

Sarah Pace

President

>Back to Top<

In Memorium: The Rev. Dr. Robert Bluford, Jr.

The Henrico County Historical Society expresses its deepest sympathy to the family of

The Rev. Dr. Robert Bluford, Jr.,

1919-2022

>Back to Top<

June Quarterly Meeting

The June meeting is scheduled for Sunday, June 5th, It starts at 2:30pm.

The meeting will be held at Deep Run Recreation Center, which is located at 9900 Ridgefield Parkway in Henrico, VA.

Our speaker will be Rachel Thayer. She will speak on the development and creation of the Sandston Historic District.

We look forward to seeing you there!

>Back to Top<

Past Presidents of Henrico County Historical Society

- Col. Oliver J. Sands, Jr. - 1975-1977

- Dr. Henry L. Nelson, Jr. - 1977-1980

- G. Garnett Haynes - 1980-1983

- Mrs. Hazel H. Tate - 1983-1987

- James. F. DuPriest, Jr. - 1987-1991

- Dr. Robert Bluford, Jr. - 1991-1993

- Beverley H. Davis - 1993-1997

- Vee J. Davis - 1997-2003

>Back to Top<

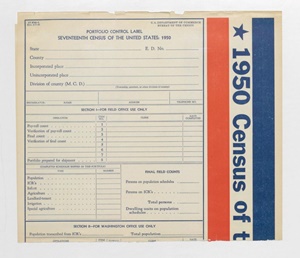

Attention Baby Boomers! The 1950 Cenus is Available Free Online

On 1 April 2022, the U.S. Census (Population Schedule) was released by the National Archives and Records Administration after 72 years. This is the first census that enumerated Baby Boomers. If you are of a certain age, you can see yourself on a census for the very first time and browse your childhood neighborhood for old friends!

Go to 1950census.archives.gov. You may choose Begin Search or Resources. You also may scroll down the page or choose from the menu for other options.

If you choose Begin Search, you will be taken to a page to complete (or partially complete) with information on the household you want to see. Enter the Location (state and city/county) and the Name (either last name or first and last name). Then select the Search icon. (If you only enter a surname, you will obtain hits of names that are similar to the ones you want.) Scroll down and look for the name you selected. Select Population Schedules for the name/household you want to read.

Click on the image to enlarge it and to browse around it or adjoining pages. Click on the three vertical dots on the top right of the image to download it. Be sure to note the Location, Enumeration District (ED) and Sheet Number for your reference or citation.

See especially Resources > Questions Asked on the 1950 Census (Not every family or person was asked some of the interesting questions).

Also see https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1950

Researcher's Note: I have been experimenting with this for several weeks, and the Search features keep changing. Also, for example, as of this writing, the list of Counties and Cities in Virginia had “Richmond.” It turned out to be Richmond City, but there is also Richmond County. The specific search feature may be somewhat different when you are searching, but it's not difficult to figure out.

Frankie Liles

>Back to Top<

Inventive Henricoans

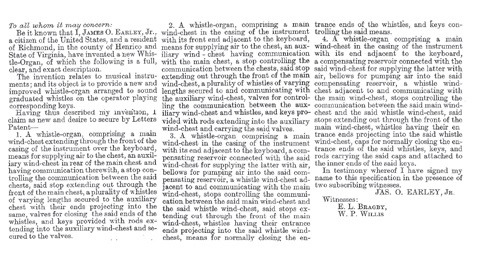

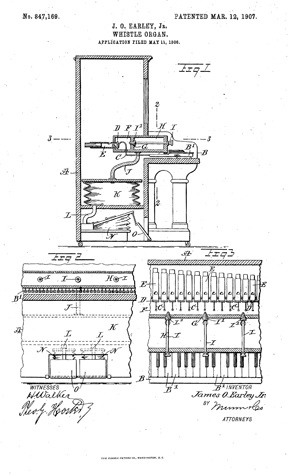

Since our last "What Do You Know?" featured a roller organ, we thought James O. Early, Jr.'s whitle organ patent was appropriate. While the full explanation is quite detailed, we have included what he claimed were his improvements on others.

>Back to Top<

1830s Henrico Witnessed a ... Short-lived Silk Craze

Here we go round the mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush.

Here we go round the mulberry bush

On a cold and frosty morning.

I can remember (barely) joining hands in a circle of fellow kindergartners as we sang this simple nineteenth century rhyme, blissfully unaware that it was anything other than a happy little ditty to dance to. I never even knew what a mulberry tree was until I lived in the Fan District and had one in the alley behind the house just a few blocks from Mulberry Street. But like so many of the simple things of youth, there may have been more behind it - a possible reference to Britain's struggle to produce silk by growing more and more mulberry trees, a key habitat of silkworms that were very sensitive to frost.

That same drive to establish sericulture (silk production) in America in the early nineteenth century produced what Amy Chambliss called "The Mulberry Craze" in her article of that title in The Georgia Review (vol. 14, no. 2). And it seems that Virginia (and, of course, Henrico County) was a bit late joining in because before the craze arrived here, Chambliss notes that "The legislatures of practically every state north of Virginia offered bounties to silk raisers."

The interest in sericulture seems to begin in Henrico around 1830, as an early advertisement under the heading "White Mulberry Tree" in the 30 September 1830 Daily Richmond Whig indicates. J. W. Smith, whose farm was four miles above Richmond, offered two-year-old Morus Alba (White Italian Mulberry trees) "by the hundred or otherwise," indicating that the season for transplanting them was approaching. He went on to note that he was "well satisfied that the silk culture must be one of the most profitable branches the agriculturist can turn his attention to. That same newspaper ad appeared regularly over at least a two-year period.

We can get an idea of the investment involved in establishing a mulberry grove for the feeding of the silkworms in a slightly different 1831 ad Smith ran. He offered white mulberry trees in the Constitutional Whig of 13 December in lots of 50 for 10 cents each, lots of 100 for 8 cents each and lots of 1,000 for 6 cents each. That translates to roughly $3.30, $2.50 and $2.00, respectively.

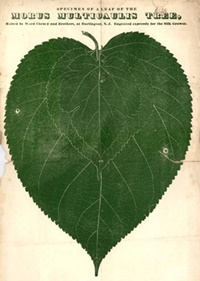

Other ads in local newspapers for mulberry trees abound over the decade from areas in and outside the state. Among the Henrico nurserymen selling the trees, we find a figure that readers of this newsletter might recall from an earlier issue: Dr. Daniel Norton, the developer of the Norton grape and the wine it produced. While Smith offered the white mulberry, Norton's ad in the 9 February Richmond Enquirer touted his "Chinese Mulberry, Morus Multicaulis, from the leaves of which, the finest silk is made."

And there was John Carter, whose Cherry Vale Nursery was on the Westham Road. According to an article in the 12 October 1838 Richmond Enquirer outlining "the introduction, mode of propagation, rise and progress of prices, and the reproduction of 'Morus Multicaulis' or Chinese Mulberry," the author (only identified as J. W) stated that Carter had begun offering the Morus Multicaulis in 1830, two years after Dr. Norton had introduced it to the area. However, the article also indicated that in 1835 "Mr. John Carter had suspended the cultivation [of Morus Multicaulis], because of the very limited demand" and that he sold 2,100 two-year-old trees to Price & Sons for 10 cents each.

Of course, silk farmers needed the silkworms that would feed on the mulberry leaves, and one Henrico resident, James O. Breeden, offered an apparently unique strain of the insect. In an advertisement in the 28 May 1839 Richmond Enquirer headed "Mammoth White Silk Worm Eggs," Breeden claimed to have 700,000 such eggs at his residence near the Baptist Seminary. That was in the area of Lombardy and Grace in Richmond, then part of Henrico County. Breeden claimed that 192 cocoons of this variety would produce a pound of chrysalis, whereas other varieties required from 300 to 350 to do so. He also invited interested parties to view the worms "now in full operation spinning their cocoons."

Once the silk raiser had his trees and eggs, he was ready to begin his operations, and sources abounded instructing the would be entrepreneur. One popular source seems to have been William Kenrick's The American Silk Growers Guide (1836). This pocket-size manual offered detailed instructions for every aspect of producing silk and was already in its second edition by 1839. Locally, newspapers carried numerous long articles outlining what they often referred to as "Silk Culture." At any rate, the basic process involved feeding the silkworm caterpillars fresh mulberry leaves. After they have matured, they begin spinning a cocoon from their spinnerets. In just a few days, the caterpillar would spin about a mile of filament, completely encasing itself. Silk farmers would kill some of them by heating the cocoons and saving some to produce the next generation. Cocoons would then be soaked in boiling water and then unwound in a continuous thread, after which a number of strands would be spun together to form silk thread.

The building that would house this process was called a cocoonery, and the 24 May 1839 Richmond Enquirer ran an article under the heading "CULTURE OF THE SILK" which described "The experiment commenced by Mr. Breeden, on the borders of our city" and added that "We have seen his small cocoonery with admiration." His mammoth white worms were about three inches long and were feeding on White Mulberry, though he had Morus Multicaulis "under way," and Breeden anticipated raising four crops in this particular season. In the 5 July Richmond Enquirer, he has a letter stating that he had sent "a skein of silk, the produce of my mammoth worms, wound from the cocoons by hand, and spun on a common spinning wheel by my lady." He went on to say that "My lady also made a skein . . . which required onehundred and sixty fibers." The editor in a note at the article's end indicated that the skein was "excellent, and beautifully dyed of a pink color."

John Carter of the earlier mentioned Cherry Vale Nursery also ran a cocoonery and was apparently considered expert enough to answer a series of eleven questions about sericulture posed by one Thomas Ritchie. Ritchie's questions and Carter's answers appeared in the 5 January 1839 edition of the Richmond Enquirer. Writing from "Sidney, (Henrico co.)," Carter answered one question as follows: "I have been in the habit of feeding a few thousand worms annually for several years past, of the two crop species–and I believe this kind is commonly preferred by those who have gone to any extent in the business. Of this kind I have reared three generations in one season."

John P. Schermerhorn, a Henrico potter featured in an earlier newsletter, also dabbled in silk raising at Montezuma, his home on the Mechanicsville Turnpike. In the 16 June 1840 Richmond Whig, he ran an advertisement indicating his desire to find "an active, intelligent Man, who is roughly acquainted with raising silk worms and reeling silk, to take charge of a cocoonery, in which the first crop has commenced spinning, and which is in successful operation, feeding upwards of a million of worms." The 11 September 1840 edition of the same paper recounted the "pleasure of examining yesterday a number of hanks of sewing silk, of every variety of dye, and of the most perfect regularity of twist, strength of texture, and brilliancy of colour which it is possible to imagine." The mulberries had been grown, the worms cultivated and the silk prepared on Schermerhorn's farm.

Perhaps Shermerhorn took his inspiration from Curtis Carter, his cocoonery-operating neighbor across the turnpike and brother to the previously mentioned John Carter. Curtis Carter was already awell-known figure before he took up farming and silk raising, and a little background about him is interesting. He had served in the War of 1812 under Thomas Mann Randolph, Thomas Jefferson's son-in-law. He was a master brick mason who had built, among other things, the Crozet House (or the Curtis Carter House) at 100 East Main Street in Richmond, a house listed on the National Register of Historic Places. He was also the lead bricklayer in the construction of a number of the pavilions bordering the Lawn at the University of Virginia. In a letter of 24 March 1819 to Nelson Barksdale, University of Virginia proctor, he and his partner William B. Phillips contract to "make & lay from seven to ten hundred Thousand Brick for the Virginia University.&wuot; It is tempting to think that the work in Charlottesville might have been facilitated by Carter's connection to Thomas Randolph; but whether it was or not, he did receive a recommendation for that work from Thomas Ritchie, who had posed the questions about silk making answered by John Carter in the Richmond Enquirer.

It is also interesting to note that Thomas Jefferson's Monticello featured the tree-lined Mulberry Row of small workshops that housed operations involved in building the estate and housing his experiments in small-scale manufacturing. One experiment apparently involved silkworms as indicated in a 3 June 1811 letter to his eleven-year-old granddaughter, Cornelia J. Randolph. He wrote, "your family of silk worms is reduced to a single individual. that is now spinning his broach. to [sic] encourage Virginia and Mary to take care of it, I tell them that as soon as they can get wedding gowns from this spinner they shall be married. I propose the same to you that, in order to hasten it's work, you may hasten home."

Jefferson's son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph, according to Maurice Robinson in The Hidden History of Richmond, "believed that 'the climate and soil of middle America' were peculiarly adapted to ‘the culture of silk'." Randolph was given permission to move into the unused arsenal at Bellona in Chesterfield County to plant mulberry trees and establish a cocoonery.

Whether or not there was a Jefferson or Randolph influence involved, Curtis Carter did maintain what was apparently a sizable cocoonery. In a sort of survey of Virginia operations, the Alexandria Gazette of 12 August 1839 noted that “Near Richmond, we have the cocoonery of Curtis Carter, Esq. that will accommodate two or three millions of worms in the course of the season.” And Carter had traveled to learn about the process. As the 4 April 1839 Richmond Enquirer indicated, "our worthy neighbor Curtis Carter on the Mechanicsville Turnpike . . . has been to the North, and has returned with such cheering lights as have induced him to make arrangements for a large cocoonery." The author promised a visit to the cocoonery and to report, and the report appeared in the 10 September 1830 issue. It describes John Carter's operation as "small scale," and goes on to say, "His very enterprising brother, Mr. Curtis Carter, is trying it on a large scale." And a large operation the cocoonery appears to have been. The Enquirer goes on to say, "It is 130 feet long by thirty feet–with two stories; and he is erecting an addition for hatching the worm and reeling the silk." It estimates Carter's costs at three to four thousand dollars and claims, "his fields of Multicaulis are the largest and most luxurious that we ever saw."

Those fields and their owner were apparently well respected as illustrated by W. M. Palmer's advertisement in the 21 December 1838 Richmond Enquirer. He noted that he still had "for sale a few genuine Morus Multicaulis Trees, Roots and Cuttings, from the Nursery of Curtis Carter, near Richmond."

But it seems those luxurious fields and the large cocoonery and others like them weren't to last a lot longer. The mulberry craze was losing momentum, as the decreasing contemporary media attention indicated. It seems as if a combination of wild speculation of mulberry trees, lingering effects of the financial panic of 1837 and exceedingly harsh winters wrought havoc on the industry. And there were hints of looming problems. The 25 July 1839 Staunton Spectator reprinted a small announcement from the New York Journal of Commerce headed "Caution to Mulberry Speculators." It read, "A gentleman who has just arrived from Mobile, having spent several months there, says there are enough Mulberry plants growing in the vicinity to supply the whole country."

Whatever the cause, Henrico sericulture faded away in the 1840s. Curtis Carter maintained his farm, where he died in 1850. But the advertisement for the sale of his personal property in the 17 September 1850 Richmond Enquirer lists furniture, all sorts of livestock, farmers utensils and a number of crops, but makes no reference to anything related to silk production. It seems as if the Henrico silk industry had seen its cold and frosty morning.

Joey Boehling

Thanks to Mary Ann Soldano for her much appreciated assistance.

Sources of silk. Pictured above are a seed packet for Maurus Multicalis (Chinese Mulberry) and a drawing of a silkworm in various stages development.

Curtis Carter's cocoonery? Jeff O'Dell's "Inventory of Early Architecture and Historic Sites" identifies this structure (no longer standing on the property owned by Carter) as possibly the cocoonery. He claims that the unusual asymmetrical fenestration supports the idea.

Carter's Land today. The Rose's store at 3000 Mechanicsville Turnpike is the site of Carter's farm. Mulberry trees, apparently a result of birds and fallen berries, still grow in the woods at the left.

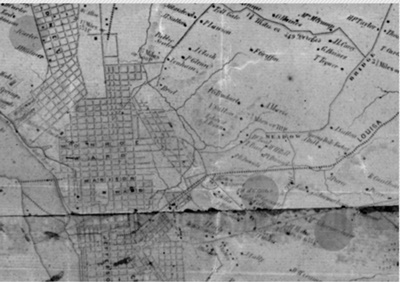

Henrico cocooneries. Marked on the map below based on Smith's 1854 survey are locations of cocooneries owned by John Carter, (1), Curtis Carter (2) and John P Shcermerhorn (3).

>Back to Top<

Now You Know: Roller Organs 'Crank Up' the Music

We congratulate Mary Jo and Haywood Wigglesworth, Anne Jackson and Tinky Keen who correctly identified the "What Do You Know?" object from the last newsletter as some kind of a pneumatic music box.

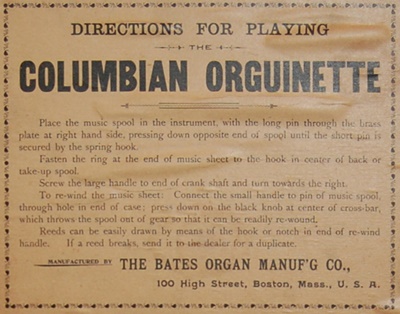

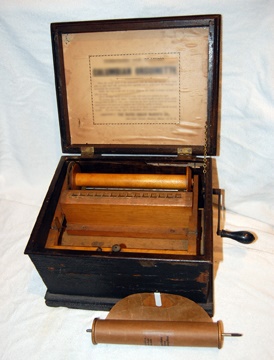

In actuality, it is an orguinette, or roller organ from the 1880s; and instructions for its use are on the label reproduced here.

As the operator turned the crank, it dragged the perforated paper from the spool across the harmonica-like portion seen below . . .

. . . while operating the bellows seen below.

The image below shows the paper roll loaded and ready to be attached to the spool that is cranked. As the holes pass over the opening, the suction created by the bellows draws air through the holes and produces the notes.

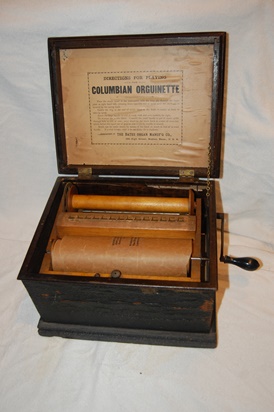

A number of different such organs were made using paper rolls, while other organs like these two . . .

a Gem Roller Organ and . . .

a Concert Roller Organ, work differently.

The cranks in both operate bellows. The Concert Organ has them in the base; while the Gem features a hinged bellows at the top, which the operator could see move up and down. Both rely on cobs like those seen in the picture of the Gem. As the cob turns, the pins in the roller come in contact with the hinged end of different organ valves. Each contacted valve lifts, allowing air into the reed chamber to produce the desired note.

>Back to Top<

What Do You Know?

This white ceramic object is 2 1/2" wide, 3" long and 2 1/2" tall. The well at the back extends to the base.

Do you know what it is?

Email your answers to jboehling@verizon.net

>Back to Top<

News 2022: Second Quarter

First Quarter | Third Quarter | Fourth Quarter

Home | Henrico | Maps | Genealogy | Preservation | Membership | Shopping | HCHS

|